ANVERS in French, ANTWERPEN in Flemish

Monday-Wednesday, April 15-17, 2019

Having left Bruges we headed east to Antwerp. We had come close to touring this city when visiting our Belgium family while checking out Bastogne and Waterloo in the fall of 2016. But, we didn’t make it as we needed to return to JUANONA to get ready to return to Maine.

This time, Antwerp was our original destination in between boat errands, yet we had added in Bruges because it was close to where we had to be Sunday. The only drawback concerned the lengths of our visits. Both seemed way too brief. We definitely could have enjoyed at least one more night, if not two, in both cities. If you’re thinking of visiting either, add on days!

Because of being short-timers here we wanted to be within easy walking distance of the sites we planned to see. And, we wanted to be able to park the car without having to pay half our room budget. AND, we wanted a comfortable place to crash with good wifi that wasn’t too expensive. Oh, and the ability to make a cup of joe in the morning… Good luck, right?

Well, we found one: “Because the Night” B&B.

Not only did our room meet all the above criteria but also included one of the warmest and most helpful hosts you could find. Paul and Ann have an inn with three rooms available in a quiet neighborhood close to the city center. He greeted us, helped us park (free on the street!), and spent time showing us the best walking routes to reach our destinations as well as pointing out some good, but inexpensive eateries (one only served spaghetti, and, boy, was it tasty and filling :). In short, we found it the perfect place for our 36-hour touring of Antwerp.

Antwerp is the unofficial capital of Flanders, the northern region of Belgium populated by predominantly Flemish (Dutch) speaking people.

Its name originates (some say) in a legend involving a Roman soldier (Silvius Brabo) and an evil giant, Druon Antigoon, a toll-keeper living in a fortress beside the Scheldt River. Antigoon would cut off the hands of those unfortunate boaters who couldn’t or wouldn’t pay the toll and toss the bodiless appendanges in the river. As you can gather, manly Brabo killed this despot and threw HIS amputated hand in the river. Now that’s a helping hand… Thus, the city carries the name derived from the Flemish word (Antwerpen) and Dutch (hand werpen) for hand throwing. Which a statue on the main square commemorates.

Considering Romans settled here in the 2nd and 3rd centuries you can see how this could be true, right? Right.

Skipping ahead 12+ centuries Antwerp became a Spanish enclave after the Netherlands won their independence from the Spanish King Philip II

whose father, Holy Roman Emperor Charles V, bequeathed him the Low Countries. Catholicism remained the official religion; yet, today similar to many Western European capitals, the city’s population features multiple religious affiliations.

Antwerp’s strength grew out of its opportunistic location of being where three rivers–the Scheldt, Meuse and Rhine–flow together into the North Sea, forming the largest estuary of Western Europe. Its growth as a shipping port, second today only to Rotterdam, began when Bruges’ water access began to silt up in the 15th century. This loss of watery transportation caused merchants and businesses to relocate east to Antwerp (reason for the title of this post). Add in the increased trade due to colonization and Spain’s exploitation of the Americas and you have a booming commercial city. Population grew five-fold from 20,000 at the end of the 14th century to 100,00 in the mid-16th century.

During this economic growth the city’s Golden Age blossomed with the Flemish School of painting. And, for those, like moi, who need a definition of this style, here it is: “Flemish painting is characterized by extraordinary subtlety, attention to detail, vivid colours, and inspired technique.” (http://www.historyofpainters.com)

With such a rich history during the 15th and 16th centuries, it’s not surprising two of the museums we targeted featured amazing feats by two local sons: a printer and an artist.

But, before we began our cultural experiences we were on the hunt for a good breakfast while walking towards our first site. We reached a small plaza where the museum stood but no cafes seemed to be open with the exception of one, only because he was waiting for a repairman. And, he only served alcohol… He did point us to the other side of the square and down a block, and, voila! the perfect spot for an excellent cup of coffee (or two) and a healthy breakfast of fruit and bread items (my type of meal). Although, Max wasn’t too keen on being the photo subject…

After satisfying our stomachs, on to food for the mind: MUSEUM PLANTIN-MORETUS.

Two friends had told us about this museum: Seppe, one of our Belgian Family members who visited it with his school group, and Deborah, one of our Dutch Family members who knew it from her touring. Two good recommend-ers.

The name comes from the founding printer, Christophe Plantin (1520-89), a Frenchman who began as a bookbinder and leather maker, and emigrated to Antwerp around 1500, Antwerp’s Golden Age.

He opened his printing shop, Officina Plantiniana, and within 20 years had expanded his business to Frankfurt, Leiden (actually he printed marine charts there), and Paris garnering the distinction of being among Europe’s industrial leaders. He operated 16 printing presses, and the museum’s collection included two of the oldest in the world (Max and I assume ‘Western’ may need to be added as a qualifier)

and employed 50 operators as well as shop assistants.

But, he definitely established a family business which included Plantin and his wife Jeanne Rivière (not the happiest looking creature) and five daughters.

During their childhood he ensured they could contribute to the family enterprise, which also included making lace, with an education in reading and writing and languages. What I found pretty wonderful was the involvement of these women in the business world. One daughter, Martine (1550-1616), begins working in the lace shop and eventually is put in charge.

Another daughter, Madeleine (1557-99), holds an important position as a proofreader for one of his major achievements, the polyglot Bible (the proofreaders’ room is pictured below and an actual sample of proofing work)

If you’re wondering about the second name of the museum, Moretus, it’s Plantin’s successor: Jan Moretus (1543-1610). He began work here at the age of 14 and became the boss’ right-hand man partly due to his language ability (he knew Dutch, Greek, Latin, Spanish, Italian, French and German) as well as his managerial skills. He also married Martine, the boss’s daughter, with whom he fathered 11 children.

Delightfully, we literally stepped and explored where these families had lived and worked. Over two floors and several hours we walked through this history.

The ground floor included a portrait gallery featuring family faces, many of which were painted by family friend Peter Paul Rubens (1577-1640). I tired to keep who was who straight but after awhile I gave up and just enjoyed gazing at the actual founders seen above, as well as influential friends, one being Justis Lipsius (1547-1606), a humanist who favored the Roman stoic Seneca (4 B.C.E.-65 C.E.).

In the painting below Lipsius (in the fur collar) is explaining a classic text with a bust of Seneca in the background and Rubens looking on.

The family kept a study for this guy, which attests to Plantin and Moretus’ honoring intellectual pursuits. Balthasar I Moretus (1547-1641), considered the intellectual of the family, printed Lipsius’ collected works of Seneca with illustrations by Rubens.

Plantin’s belief was ‘With hard work, perseverance and patience one is able to surmount any hardship.’ He did experience hardships throughout his career (one being when he had all his possessions auctioned off due to a run-in with the authorities). Yet, he lived by his motto and continued to build his business with the bulk of the Plantin’s printing featured religion (35%), Humanism and Literation (35%), Science (10%), Governmental publications (8.5%), Pamphlets (4.5%), and Other (7%).

He also knew how to network, acquiring the lucrative contract as the appointed typographer royal to King Philip II of Spain (the one who fought William I of the Netherlands at the beginning of the Eighty Years War). It was with the death of Philip II’s father, Charles V, that helped Plantin establish his reputation with a book covering the 1558 funeral procession (also sold as a 12-meter roll). It was printed in the five languages (Dutch, French, German, Spanish, and Italian) spoken in the Holy Roman Empire.

Although he printed for the Catholic King, including the church’s Index of Prohibited Books in 1569*,

he also was a businessman who would print competing religious teachings, such as Hendrik Barrefelt’s preaching of tolerance in 1584. But, Plantin wasn’t stupid: he did so using the pseudonym Jacobus Villanus.

* This listing of banned books began in 1559 and didn’t end until 1966 (!).

In addition to the humanist and religious works the company published atlases by Abraham Ortelius (1527-98). Ortelius first atlas contained 53 maps, growing to 117 eight years later. Because maps were printed individually one could build their own atlas based on which maps they collected.

‘Atlas’, by the way, is a term first coined by Gerard Mercator whose maps would eventually be seen as more accurate than Ortelius’.

Plantin and his successors kept a competitive edge by constantly improving the printed word. He would use engravings over woodcuts to ensure a better quality of illustration.

And, typography was another of the company’s key strengths. He used the best designers for his typefaces (for example, Robert Granjon’s modern Times New Roman and Claude Garamont’s Garamond), and he ensured no other printer could use them because Plantin literally owned the metal type. Eventually, the company had 90 fonts enabling them to print in a variety of languages, which they did: Latin (62%), Dutch (14%), French (14%), Greek (5%), Spanish (2%), Hebrew (2%), and ‘Other’ comprised of German, Italian, English, Old Syriac, and Aramaic (1.8%). The typefaces were stored in large wall drawers.

Balthasar, mentioned earlier, went one step further by building a foundry which operated between 1622-60 and 1736-60.

A staff member–who saw us peering at minute type with quizzical expressionswondering how the hell did they do that?!–

kindly explained some of the printing and fonts. He asked us why capital letters were called ‘upper case’? It’s because they stored those less-frequently-used letters in the upper case of the cabinet holding the alphabet of a particular font.

To ease the arm movement of the typesetters they placed the most commonly used letters in the lower center to avoid unnecessary movements.

Plantin’s masterpiece was the Biblia polyglotta or Biblia regia. Under the sponsorship of King Phillip II (who sent theologian Benedictus Arias Montanus to overseer it), this work composed of eight volumes gained international fame. An original set shows the interesting clasps used to bind them.

During our wanderings I discovered quite a few business women assisted in running this business, such as Anna Good (1624-1691)… Anna Maria de Neuf (1654-1714) who grows the business during difficult times… and, Maria Theresa Borrekens (1728-1797) who married François-Jean Moretus.

Nine generations of this family managed to produce amazing work. Edward Moretus (1804-80), grandson of Maria and François-Jean mentioned above, publishing the last book, the breviary of Saint Francis. He sold the house and contents, including a rare musical instrument–a combination of a harpsichord and virginal (one of the only four known in the world),

to the city who, thankfully, turns it into a museum.

By now my eyes are rolling sloppily in my head and I’m feeling very, very uneducated and, definitely, not very linguistic. But, wow, did this museum exceed all expectations.

It wasn’t all serious pondering. We managed to get into the spirit of it all when I persuaded Max (didn’t take much) to don an outfit of the time…

After lunch at a laundromat (great idea and one my sister and a friend almost started),

we headed for our second museum of the day, RUEBENSHUIS. In actuality, a mansion.

Unlike Plantin’s abode, Peter Paul Rubens’ home didn’t survive the four centuries without major renovations by subsequent owners. The only remaining parts are those Rubens, himself, commissioned: the garden portico and the garden pavilion, heavily influenced by his study in Rome.

Yet, the ‘house’ Rubens inhabited beginning in 1610 until his death 30 years later definitely felt like he’d been there.

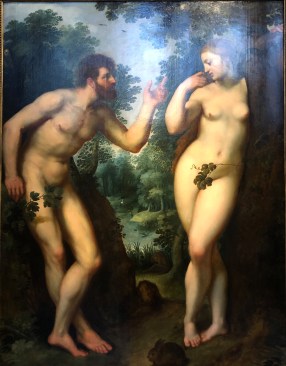

Although he was born to a Calvinist father who fled with his family from the Southern Netherlands to avoid religious persecution, Rubens was raised a Catholic (his mother’s religion) after his father’s death in 1587. With a classical education and apprenticeship to Antwerp’s leading artist, Otto van Veen (1557-1629)– one of Ruben’s earliest paintings (of Adam and Eve) reflects van Veen’s influence with the use of cool blue and green color hues as well as a more static background –

Rubens eventually left for Italy in 1600 where he continued to perfect his talent, marrying the styles of Renaissance to Baroque.

When he returned to Antwerp in 1608 he gained local fame with his 1609 commission Adoration of the Magi for the Town Hall, which found its way to the King of Spain in Madrid in 1628 (now in Madrid’s Prada Museum).

Like Plantin, Rubens obtained the patronage of royalty, the Hapsburg regents Archduke Albert and Archduchess Isabella, enabling him to amass even more wealth. At the time of his death he owned this mansion and several country properties.

His studio became the largest and best known in Europe, helping him to become a superstar at the time of his death.

We learned apprentices would use Rubens’ preliminary oil sketches to do the large scale versions. Then Rubens would fine-tune the most important elements–people and flesh tones. Yet, the master painted the entire piece of his most important commissions.

One of his most successful apprentices was Anthony van Dyck (1599-1641) who became more of a collaborator with Rubens as opposed to pupil. Later considered a rival to his teacher, Van Dyck became a court painter to Charles I in London, who knighted him in 1632. Below is a portrait by van Dyck.

Royalty is definitely one’s ticket to success…

We meandered with a small booklet through rooms showcasing a variety of paintings, Rubens’ as well as his contemporaries’.

Later, in reading about this artist it’s not surprising he became a friend of Plantin and other famous residents of the city. Rubens spoke five languages, was a scholar, a humanist, a diplomat and possessed extraordinary energy.

Speaking of energy, ours was flagging. We had filled our heads with the art of printing and of oil painting, both fields represented by two genuises, one I had heard of and one I hadn’t. Time for that full plate of spaghetti, bed, and home to JUANONA.

With a stop for a libation

in the shadow of the cathedral,

we slowly strolled back to our B&B stopping to gaze at some art along the way.

Unfortunately, we missed touring a third site on our list, the Red Star Line Museum covering the emigration of several million folks to Canada and the United States between 1837 and 1934. We learned afterwards what a mistake this was when two friends told us how rewarding their visit thad been.

Next time, for Antwerp along with Bruges and other historical, thriving places are on our list for repeat visits.

Now, back to JUANONA and prepping her for summer cruising… and a visitor!

Awesome post, Lynnie. Great to visit Antwerp with you and Max! xoxo

Cool city and some amazing museums. I hope Idaho is treating you well, Carolie! Xxo

HOLA!

Loving the post – especially the Libations!! Great word!

Looking forward to watching where you go next

X

And, where you go! Are you in Cartagena? Xo