Tuesday-Tuesday, June 6-13

NASJONALGALLERIET (National Gallery)

I never thought I’d be an art-museum hound but I’m definitely becoming one. With Oslo offering so many tantalizing sites we had to pick and choose where we went, which is how we ended up in front of the imposing 1882-built Nasjonalgalleriet on a Thursday.

We joined a horde streaming through the front door and showed the ticketers our Oslo Pass only to discover Thursday is a free day.

With our audio guides we climbed to the 1st floor (what we’d call 2nd floor) and began our walk through 20+ rooms of art history. As we entered each gallery a brief description introduced us to the time period. We skipped some of the earlier rooms so we could concentrate on the 19th and 20th century artists.

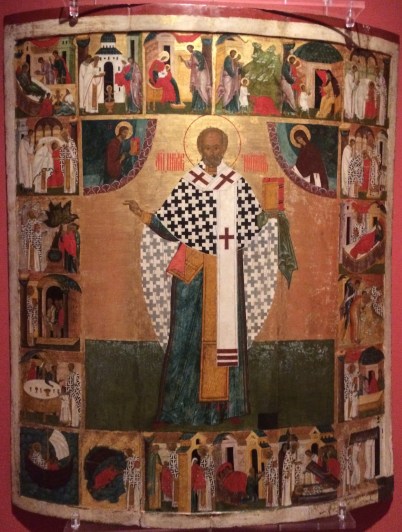

But, I did make one exception when I noticed they had some Russian icons, one of Saint Nicholas of Zaraysk, the patron saint of travellers, children, and sailors. The audio guide indicated it exemplifies the style of the Novgorod School. Immediately my connection antenna shot up. This Russian town became the east-meets-west trading zone back in the 11th century . Dutch, German, and Scandinavian merchants congregated at this crossroads where they bartered and sold goods from their countries with those travelling up from the Silk Road.

This icon was painted by an artist from the 14th/15th century using “…clear and pure colours, narrative elements [20 scenes depict St. Nick’s life], expressive lines, and contrasting monchromatic fields.” Sounds good to me. I just liked the historical association.

This museum had a sampling of other artists, such as El Greco’s (1541-1614) St. Peter, Jan van der Heyden’s (1637-1712) The Old Church in Delft, Francisco de Goya’s (1746-1828) Portrait of a Picador, and notable works by Picasso and Modiglani; but, as mentioned above, I skimmed through those rooms.

Having been fortunate to visit Bergen’s Kunstmuseum (KODE) last summer, we had acquainted ourselves with some of Norway’s artists. These were whose works I eagerly anticipated; and, I wasn’t disappointed.

So, let me take you on a brief tour and see if you, too, have a favorite among these artists.

1810-1840 Romantic Landscape Painting

The rise of the middle class steered artists away from the bible and historical themes towards nature. Partly this yearning for the balm of nature arose due to industrialization, which makes sense to me.

One of Norway’s premier artists of this time is John Christian Dahl (1788-1857). Called the “father of Norwegian Landscape Painting” he spent his childhood in Bergen but settled in Dresden, making a name for himself and acquiring international fame; the first Norwegian artist to do so.

After staring at the rainbow, if you look closely you’ll notice this typical landscape “View from Stalheim” includes vignettes of those living and working amidst these mountains.

Later, in another room I saw a number of his studies he did for his final pieces:

1830-1879 Norwegian Landscape Painting after Dahl

Well, you know you’ve made it big when a period of art history is termed “after” you. These guys followed in Dahl’s brush strokes (sorry, couldn’t resist). They obviously learned a lot.

Thomas Fearnley (1802-1847) “Old Birch Tree at Sognefjord”

Peder Balke (1804-1887) “Stetind in Fog”

Amaldus Nielsen (1838-1932) (In Madal we saw a bust of his by his fellow Mandalite, the famous sculptor Gustave Vigeland) “Farmhouse at Balestrand”

1848-1879 Norwegian Scenes Painted in Germany

With no Academy of Fine Arts in their country, many Norwegians travelled to Dusseldorf to study at this time. Munich, too, offered an opportunity to study old masterpieces. Here I recognized an artist whose home town we visited earlier in our cruise:

Adolph Tidemand (1814-1876) with Hans Gude (1825-1903) “Bridal Procession on the Hardangerfjord” feels like a fairytale to me. And, it’s a familiar one considering its the frontispiece of our guide book.

Tidemand’s “Low Church Devotion” portrays Hans Nielsen Hauge preaching when it was outlawed for a lay minister to do so.

Eillif Peterssen (1852-1928) Here, too, I noticed a portrait whose blend of a historical scene (“Christian II signing the Death Warrant of nobleman Torben Oxe” in 1517) and artistic skill drew me in.

I mean, look how his wife, Queen Isabella, begs him not to sign. Interestingly, since Oxe was accused of murdering the king’s mistress (and was later beheaded). Isabella must have sensed the danger of the king doing so, as the curator noted this act indirectly ended Christian II’s rule.

1880-1910 Realism and Outdoor Painting in Nordic Art

During this time Norwegian artists travelled to that art capital of the world, Paris, for lessons from the outdoor painters (thanks to my artists friends I know that’s called “en plain air”). Realism and the struggles of everyday life framed their work.

Erik Werenskiod (1855-1938) who painted country life like “Peasant Burial” and the two young girls featured at the beginning of this post.

Christian Krohg (1852-1925) “Albertine to see the Police Surgeon” speaks to the double standard of Kristiania’s authorities regarding prostitution and the mandatory medical exam. The artist/novelist’s book “Albertine (1886) was banned but this painting attracted thousands of viewers when on exhibit one year later. He reminds me of Victor Hugo and Charles Dickens who addressed contemporary social issues through fiction.

Yet, Krohg also captured domestic scenes, such as this with the mother falling into an exhausted sleep after her child has fallen into one of contentment…

Anders Zorn (1860-1920) His painting, “In the Skerries”, takes us outside with a young woman enjoying an (obviously) warm summer day.

1880-1910 Interiors and Portraits in Nordic Art

Moving from outdoors to indoors, Nordic artists painted scenes of ordinary people with family and friends serving as models.

Harriet Backer (1845-1932) I always notice female artists, Backer being one of them in this museum. In her “Blue Interior” I can see myself sitting opposite this relaxed woman as she tends to her mending.

Halfdan Egedius (1877-1899) On the other hand, looking at “Portrait of Mari Closen” I do not think I’d be keeping this woman company…

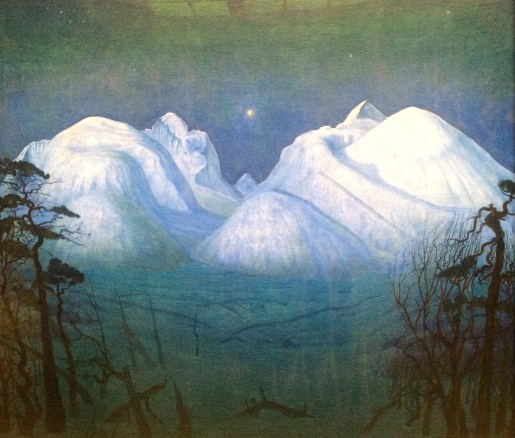

Harald Sohlberg‘s (1869-1935) “Winter in the Mountains” captures his experience of skiing in the Norwegian mountains 1899. He said it best when he likened it to “…being beneath the lofty vaults of a cathedral, only a thousand times stronger.” If you look in the upper right you’ll see how he memorialized this experience with a cross.

Speaking of female artists, the National Gallery recently acquired a self-portrait by Leis Schjelderup (1956-1933), one the museum describes as ‘a precious gem’. They now own four of her paintings.

A Pioneer in Early Modernism: Edvard Munch (1863-1944)

No matter your age or level of art appreciation, most people know this guy. I’ll let the intro to his room provide the background on him and his art:

Why I said his name is so well-known (If the area hadn’t been so congested you’d see me doing the same)…

“The Sick Child”…

and his “Madonna” portrait. A bit different from the ones I’ve seen in churches.

1900-1920 Norwegian Impressionism and Expressionism

How could an artist not be influenced by Edvard Munch? And, by the contemporary French art scene, especially after studying there?

Nikolai Astrup (1880-1928) The KODE Museum in Bergen had a special exhibit on his life and work. Background information enriches the viewing, especially when points of connection tie an artist to others: in this case, Erik Werenskiod; Harriet Backer; and, John Constable.

Jens Ferdinand Willumsen (1863-1958) (Danish artist) “After the Tempest”, which is on a frame he created.

My last room featured an artist known for his storybook illustrations, Theodor Kittelsen (1857-1914). I had learned he was from Kragero, where we had walked the Munch walk. Years ago I began collecting children’s book because of the art work. I definitely would have wanted one of Kittelsen’s. Call me sentimental, romantic, stuck-in-fairytale dust, but these are enchanting.

With sighs of contentment we exited this fabulous gallery, one not too big, not too small but just right. And, definitely worth a repeat visit.

RADHUSET (CITY HALL)

Pairing a National Gallery with a city hall may seem odd until you step inside Oslo’s.

Recommended by fellow cruisers, Dick and Ginger, as well as others, we visited what at first sight seems like a red brick factory.

However, as we approached the entrance my outlook starting changing. The creation of this structure created controversy due to its location (a slum district in 1913), but the mayor persisted and a 1918 competition resulted in two architects designing a medieval-style building with a tower. By 1930 modifications altered the plans to create a modernistic appearance. WWII interrupted the construction, which was completed in 1950 revealing a big, dark brown monolith.

Like the architectural design, a contest was held for the interior decoration. The winning artists began work in the late 1930s into 1942/43 until the Nazis’ occupation halted the work, sending some of the artists to labor camps. The work finished after the war, and what an amazing place to walk into.

Room after room presents Norway’s history in colorful murals, tapestries, and paintings. As you enter each room you’re provided with details on the decor, from paintings to construction materials to furniture to curtains.

How can you not be enthralled by the glorious art adorning the walls when you walk into this…

The Radhushallen (the grand function room)?

The mural by Henrik Sorensen, reputedly the largest in Europe, covers the back wall while complimentary ones dress the others. A glorious setting for awarding the recipient of the Nobel Peace Prize, which is done in this room.

Other rooms offer similar desserts all blending into a wonderland of modernistic design …

The Hardrade Room is named after King Hardrade (1015-1066). One tapestry depicts a historical event: the Battle of Stamford where he lost to the English King Harold II, who was subsequently beaten less than three weeks later at the Battle of Hastings by William the Conquerer, who, by the way, was descended from Rollo, the Viking who sacked Paris (885-6) and is sometimes called the 1st Duke of Normandy.

Opposite, the second tapestry places the king in Oslo amidst builders and courtiers symbolizing the city’s founding. To commemorate this date, the Radhuset opened in 1950, Oslo’s 900th anniversary.

The Munch Room honors Norway’s most famous painter with his painting, The Tree of Life (1910), which may have been painted when he was living in Kragero.

Press conferences, small reception lunches and dinners are held here as well as civil marriage ceremonies one Saturday a month.

The Banqueting Hall is noted as ‘the grandest of all the function rooms’ with four Norwegian monarchs: King Harald V (1937), Queen Sonja (1937),

King Olav V (1903-1991), and King Haakon VII (1872-1957) who became Norway’s first Norwegian king post-dissolution of the union with Sweden in 1905. But, what really dominates the room entirely covers the north-facing wall: the painting by Willi Midelfart of a summer scene. As Max noted, what other country would refreshingly mix royal portaits with nude sunbathers?

The Krohg Room (East Gallery) is used for city council meetings and political events, the room is drenched in colors painted by the artist Per Krogh’s (son of Christian Krogh).

Each segment of his murals symbolize an aspect of Norwegian culture, such as the bees (bottom left) embodying the interelationship between the city (the hive) and the countryside (rosebush).

While on another he paints scense of everyday life in Norway.

The Storstein Room (West Gallery) features “Human Rights” by Aage Storstein traces the evolution of Norway’s path to its constitution. Due to the richness of the story I’ve included the description we read unpon entering so you, too, can be enveloped in this tale.

Our last room turned into a hallway with glass cases holding various gifts from foreign nations and historical items, one being a 1427 medal of Oslo’s city seal featuring Saint Hallvard (1020-1044).

The design displays the elements of his story. A son of a weathy landholder, Hallvard tired to rescue a pregnant woman (the one lying in front of him); but, both of them were killed; Hallvard by three arrows (held in his left hand), when caught by the pursuing group of thugs. Realizing they’d murdered a high-born son, the thugs threw him into the wate weighted down with a millstone (held in his other hand); but, both he and the millstone floated to the surface (right…) and, voila, a Saint was born.

The tale is also depicted on manhole covers. (With municipalities decorating utilitarian items such as these, it’s no wonder our friend Ellen is collecting their images.)

May 15th, two days before Norway’s Constitution day, is his memorial day, often called “Oslo Day”. The seal was designed in 1924 when the city’s name reverted from Christiania/Kristiania, named after the Danish-Norwegian King Christian IV, to its original name, Oslo. Being independent (as of 1905) Norwegians wanted to honor their country’s history.

“Oslo stands unanimous and constant” surrounds Saint Hallvard, which, I have to say, is a refreshing statement considering the current state of affairs in the USA of partisanship and uncertainty.

What a great city in which to live.

Stay tuned for a glimpse of another Norwegian icon…

It looks like your next life will be as a college professor

Hah! Only if teachers are allowed to make tons of mistakes and have a computer and GOOGLE at hand :)