78°13’24.02″N, 15°38’48.8″E

(Longyearbyen, on Spitsbergen Island, SVALBARD ARCHIPELAGO)

Thursday-Thursday, December 22-28

Okay, we’re not going home for the holidays. No one is heading over here. So, what to do?

Why, go north, of course! Which is how we ended up in the Svalbard Archipelago on Spitsbergen, in a town 814 miles from the North Pole.

No, we didn’t spot any jolly guy driving a reindeer-sleigh across the sky, although, there is a mailbox for him. Yes, it was cold, but not too cold at all (10 to 30 degrees). And, yes it was dark (24-hours). But, boy, was it AMAZING!

Thanks to warm air coming from the south and an offshoot of the Gulf Stream (West Spitsbergen Current) it’s not that cold, or not as cold as one would think.

Compared to other Arctic lands, the relatively mild climate offers sustenance for marine life, birds, and land mammals in spite of half being covered by glaciers and the other half pretty barren. We couldn’t really see the landscape it being dark and all, but we read the view is similar to what it had been at the end of the last ice age.

Having friends who sailed here during summer months we have toyed with the idea of doing the same; but, the vast distance to sail would require wintering over in Tromsø or some other Norwegian port due to the short cruising season.

Visiting here in the winter came about thanks to our Swedish friend Michael’s enthusiastic description of his time here last January. Flying in seemed a lot more practical (and easier) than traveling by boat, and a wintery wonderland for Christmas appealed to our interest in exotic locations. Which is how we became two of the roughly 600,000 annual visitors to Spitsbergen with 50% of those passengers arriving on summer cruise ships.

With backpacks stuffed with warm outfits but no sunglasses (I reminded Max he didn’t need his after he packed them) we flew from Amsterdam to Longyearbyen. We had to overnight in Copenhagen due to limited, connecting flights to Svalbard. Fortunately, we decided to book a hotel room as otherwise this would have been us (which has been us in the past)…

and, could be us in the future for as Max observed “doesn’t look too bad because you can actually stretch out”…

Because the Svalbard Archipelago isn’t part of the Schengen agreement* (or EU), we had to go through passport control when entering and leaving.

* The 1985 Schengen Agreement–named for where it was signed in Luxembourg–removed the European border checks for those citizens whose country signed this treaty. Almost all the EU countries signed (with Great Britain being one which didn’t). For citizens of non-Schengen countries, you’re only allowed up to three cumulative months in Schengen countries after which you must leave for three months. We’re allowed to stay due to our application and acceptance for temporary Dutch residency under the Dutch American Friendship Treaty (DAFT).

With growing tourism over the past 15 years the plane was packed with excited folk like us, and, when we landed in pitch black we joined them snapping shots of our winter destination.

The airport crews joined in the fun

and locals welcomed arrivals with hot glogg (Glühwein) and crisp cookies.

Another greeter was a vision in white and one I never wanted to be this close to:

Svalbard Hotell & Lodge, Longyearbyen’s newest accommodations, became our home over the next six days, and what a great place to enjoy what the area offers.

Due to our assigned room’s reading lights not working, Jason upgraded us to a suite (!), which included our own Nespresso machine :) We always felt welcomed by the reception manager Ana and her staff, several of whom we met such as Christiana from outside of Newcastle, England and Alexander from Russia.

Ana moved here from Tromsø with her family when she was seven and told of being in elementary school where she was one of two classmates in her grade. She was helpful, friendly, and extremely patient -as were all of her staff- as every hotel guest, us included, asked about the likelihood of seeing the Northern Lights. This obviously was THE question as we gazed at the board right above their heads, displaying the real-time strength of the aurora borealis.

One aspect of our trip did surprise us: the excellent meals at the hotel’s restaurant. As Max commented “Who would have thought to come here for the food?!” The breakfasts were superb with an a la carte spread of yogurts, power shakes, fresh-cut fruit, cereals, cheeses, meats, lettuce & tomatoes, pastries, breads, eggs, bacon, and plenty of condiments and spreads as well as juice, coffee, tea and water. And, yes, we did make sandwiches for our lunches a few times.

Luckily we reserved a spot for Christmas Eve dinner here; and, we feasted on a mouth-watering buffet compliments of Christian’s husband, Grace, who hails from Oban, Scotland, and is the hotel’s chef.

For Christmas Day dinner we opted for another restaurant, the Nansen (named after Fridtjof Nansen, 1862-1930, a famous Norwegian polar explorer), located at the Radisson Blu Hotel, and the only other eatery open that day. Max ordered the “Arctic Special” consisting of whale, seal, and reindeer meat, not a particularly PC meal (and, sorry about the seal, Andrea!). No, none tasted like chicken, and, yes, the seal tasted a bit fishy.

Before I move on from the food and hotels, an interesting fact is the Svalbard Hotell & Lodge’s link to another one of Norway’s polar explorers, Eivind Astrup (1871-1895) whose statue greets you close to the entrance.

Unless you’re an avid reader of polar exploits, you may not be aware of how his pioneering of dogsleds and skis dramatically altered Arctic explorations. As you can see, the wooden version is a good likeness!

The hotel’s founder is a descendent of Astrup, which explains why the restaurant is named Polfareren (polar explorer) and why Astrup’s framed mapping tools and diary hung on the restaurant’s wall. Couldn’t have been a more fitting place to stay considering Max’s keen interest in polar exploration.

The tales of this land fascinated me, which means the following is a brief bit of history about this area supplemented by our visit to the Svalbard Museum:

As a land of rocks and permafrost, Svalbard is an Arctic Tundra with no trees, no forests, no agricultural areas, and few species of flora and fauna; however, before its ground became permanently frozen, some dinosaurs did inhabit this land and these waters (Svalbard was submerged for millions of years). In the early part of this century, they discovered fossils of swan reptiles (plesiosaurs) and fish lizards (ichthyosaurs) in Svalbard.

Those animals existed during the Jurassic period and were later replaced by those more suited to an Ice Age.

Fast forward millions of years to 1194 when the name ‘Svalbard’ (‘Cold Coasts’) was first mentioned in Icelandic annals, although not necessarily meaning this specific group of islands. In 1596 when searching for a North-East route over Siberia the Dutch explorer Willem Barentsz formally discovered the largest island of this archipelago and named it Spitsbergen, Dutch for ‘jagged mountains’.

During the 17th century these waters became whale-hunting grounds for Danes, Dutch, Norwegians, English, Germans, French, and Spanish with Russians joining in at the beginning of the 18th century thanks to Tsar Peter the Great’s desire to expand his realm. With no international restrictions, these nations harpooned the valuable Greenland right whales (or bowhead whales) to the point of extinction.

Graves provide proof of these early visitors and the dangerous lives they led…

with display cases exhibiting some of the items found:

this wide-brimmed hat…

woolen cap…

blue coat…

blue coat…

and, leather shoes.

With the decline of whaling, the 19th century brought hunters and trappers. Until the mid-1800s the Pomors (from Russia’s White Sea coast), familiar with Arctic grounds since the 1700s, focused on catching walrus during the summer. In winter months, when the weather didn’t allow hunting, they entertained themselves with games and handicrafts. At Svalbard’s Museum we saw some of the artifacts from their time here, such as these crosses.

Arctic foxes,

reindeer,

and polar bears

became the main quarry for hunters and trappers from the end of the 1890s to 1941.

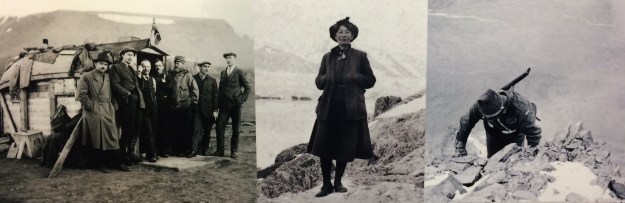

And, they were some hardy folk. Imagine calling this ‘home’?

Posh tourists and adventurers also travelled to this northern land to enjoy the great outdoors.

In addition to the larger game, seals, birds, duck and goose down added extra income to the 400 or so inhabitants (6% being female) during the first half of the 20th century. With plenty of space and animals to hunt, Svalbard stayed a terra nullius or no-man’s land unfettered from any one-country’s domination. However, this changed due to the discovery of coal in the 19th century.

Between 1898 and 1920 coal miners registered over 100 claims. With the resource now in the land versus roaming around it, it became necessary to clarify ownership and settle disputes regarding these claims. The Spitsbergen Treaty was drawn up and signed in 1920 giving Norway sovereignty over Svalbard.

Since the original 14 countries signed the agreement [Denmark, France, Italy, Japan, the Netherlands, Norway, Sweden, United States, the UK (including Australia, Canada, New Zealand, Newfoundland, and South Africa)] 22 more countries have added their signatures to the treaty, the most recent being North Korea in 2016.

Although Svalbard is under Norwegian administration and law, all citizens of the signatory nations have free access to live, work, and trade here. Taxes are substantially less than mainland Norway’s (16% vs. 40%) and collected for the sole use of Svalbard’s administration. Additionally, no military operations are allowed.

Currently Norway and Russia operate coal mines on Svalbard, subsidizing the operations to maintain permanent settlements on this arctic land. For a lengthy but fascinating explanation on Svalbard’s evolution from 1925 to the 21st century, click here.

We stayed in Longyearbyen, Spitsbergen’s largest permanent settlement with 2,200 population, about 70% being Norwegian with the remaining being multinationals. Due to tourism English is becoming the de facto language, which made it easy to visit this icy land.

The other towns are: Ny Ålesund, an international research station with about 40 people*; Barentsburg, a Russian coal mining town, population around 400; and, Sveagrua, a Norwegian coal mining town with an uncertain future. A few weather stations also are sited on Spitsbergen and other Svalbard islands.

*The famous Norwegian explorer, Raold Amundsen, explored the Arctic with airships in 1926 and 1928 using Ny Ålesund as his base.

Longyearbyen is named after Michiganite John M. Longyear, an American businessman, who visited Spitsbergen on vacation in 1901 (back then this was a destination for the elite). He returned several years later after analysis of some coal proved it to be of the highest quality. An astute business man, Longyear and fellow investor Frederick Ayer established the American Arctic Coal Company. The AACC began mining coal in 1906.

Just a side note… Longyear and his wife Mary moved to Boston in 1899, dismantling their stone mansion in Marquette, Michigan, and moving it lock, stock, and barrel to Massachusetts to please Mary. Mary’s interest in the Christian Science Religion resulted in her home becoming a museum dedicated to the teachings of Mrs. Mary Baker Eddy. The museum moved to a new location on Chestnut Hill in 1998 with the Longyear mansion becoming, what else: condos.

Back to the Arctic tale… For ten years AACC mined coal until selling the company to a new entity, the Norwegian mining company Store Norske Spitsbergen Kulkompani (SNSK), in 1916. Store Norske became the dominant coal enterprise, buying other companies as they came up for sale and eventually becoming 100% state-owned. As this Norwegian company grew, Longyearbyen became a ‘company town.’ Store Norske even issued its own currency: ‘Spitsbergen money’ in the form of wage vouchers until 1980 (!).

A total of ten mines have operated on Spitsbergen between the early 1900s and today: Norway’s Store Norske owned eight; and Russia’s Arktikugol Trust (also state-owned), two. Currently only two of them are still operating: Norway’s Mine 7 and Russia’s Barentsburg. NOTE: SNSG is a subsidiary of SNSK.

During our visit we met locals who spoke of the current dilemma facing their community. With Norway going ‘green’ the politicians in Oslo want to close down the coal mining operations, temporarily leaving Mine 7 still operating. The coal is used by the local power plant as well as exported for energy usage and making high-quality steel parts (BMW and Mercedes use it in manufacturing their cars).

Locals, however, want to re-open one of the closed mines–Lunckefjellet, near Sveagruva. Originally Swedish, it was purchased by Store Norske in 1932, and irregular operations continued; but, as of 2014 this mine was only kept in standby mode. To permanently close it will cost about $1 billion; yet, with the rising price for coal, some investors say they can operate the mine for less than the cost to close it. And, this is the richest coal vein for Store Norske.

Ironically, one local told us the head of Longyearbyen’s Local Government drives a ‘green’ car, a Tesla, whose battery is charged by coal…

If Norway decides to shut down all of the island’s coal production to (a) stop subsidizing the operations and (b) go completely green, Spitsbergen would have to import ‘dirty’ coal. Actually, they’ll have to import coal in about ten years anyway because that’s the amount of reserves remaining in Mine 7 (unless they go re-open Lunckefjellet).

With the gradual closing of mines locals say the community has changed. They didn’t say how but I’m surmising the area feels less cohesive than one dependent on a single industry. The government wants to build up other economic activities including tourism, research and higher education. Regarding education, UNIS, The University Centre in Svalbard, opened in 1993 and currently has 759 students (50% Norwegian and 50% International) with all courses taught in English. Tuition is free and the focus is on Arctic biology, geology, geophysics, and technology with degrees from undergraduate to postgraduate. If you like snow (or ice), sounds like a great place to get a diploma (which is how Christina, who worked at our hotel, ended up here).

It will be interesting to see how Norway and Spitsbergen resolve this issue. Svalbard is an important strategic foothold in the Arctic, with both Norway and Russia having subsidized their coal operations for that reason. Although the 1920 Svalbard Treaty doesn’t allow any military activity, Norway views Svalbard as a military presence in the Arctic. Meanwhile, Russia has been expanding its military base in the nearby Franz Josef Archipelago.

Furthermore, if these two countries do end up closing down their mines, other countries may decide to move in. Case in point–in 1910 Russia bought the Pyramiden mine (closed in 1998) from Sweden, and the Barentsburg one, still operating, from the Dutch in 1932. Hmmmm, can anyone say “North Korea”?

Next: why we enjoyed Longyearbyen so much :)

Lynnie, you and Max are probably going to be professors when ever you do return to the states. I love your posts

Thanks, Scott, and Happy New Year to you and Kitty! xo